Applying lessons from the Swiss school system to development cooperation

A solid school education is crucial to development. The Swiss school system is highly regarded and has considerable as yet underused potential to serve as an inspiration for development cooperation work. That is about to change. Switzerland creates added value in developing countries and can help shape educational agendas, says Sabina Handschin, education expert at the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), in this interview.

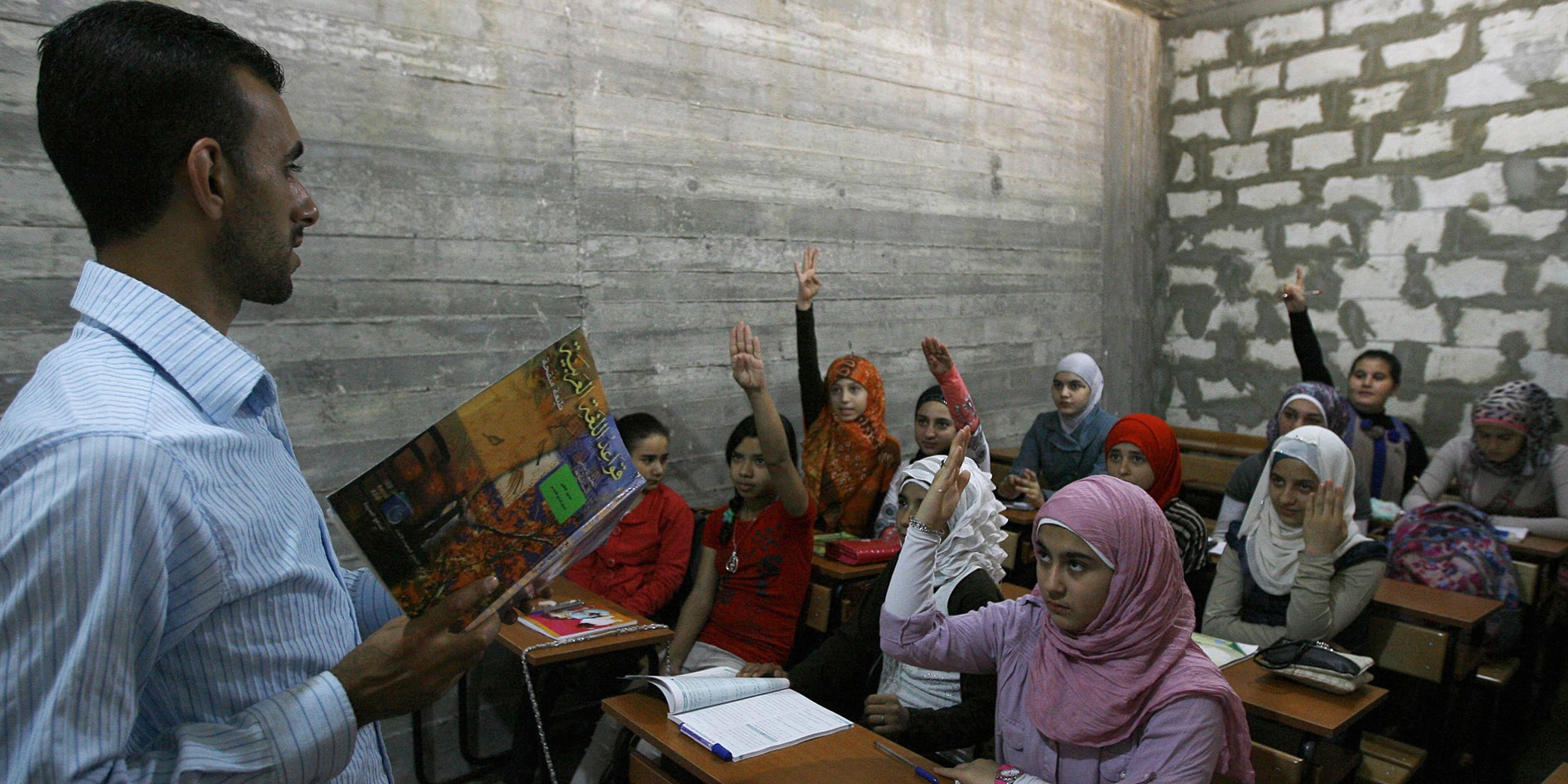

Everyday life in a school for Syrian refugees in Lebanon. © Keystone

Even in the face of the war in Ukraine, Switzerland's international cooperation (IC) is committed to ensuring that children in Ukraine continue to have access to education. For example, the online learning programme launched for Ukrainian schools during the COVID-19 pandemic will continue to enable children to learn remotely and prevent them from falling behind.

This is just one topical example which illustrates the key role played by primary and secondary education in Swiss international cooperation. On 26 April 2022, the SDC, together with Movetia, the national agency for the promotion of exchanges and mobility in the education system, organised a conference on the 'Strategic Role of Swiss School Education for International Cooperation'. The aim of the conference was to raise awareness of ways to apply the special strengths of the Swiss school system to bring added value to development cooperation and to discuss how experiences from the Swiss school system can be used more strategically and effectively in Swiss international cooperation in the future.

In this interview, education expert Sabina Handschin explains what the SDC is doing to put these insights into practice.

What does it mean to apply Swiss school education expertise in another country? Is Switzerland exporting its education system to other contexts?

We don't talk about exporting, we talk about inspiring. The Swiss education system is objectively considered to be one of the best in the world. And when compared internationally, our compulsory school system offers many advantages that can be a source of inspiration for ministries of education and other education authorities in SDC partner countries.

To give you an example: when I was in Lebanon I met representatives of the ministry of education. Lebanon's state education system is stretched to the limit, not least because of a large influx of refugees from Syria. At this meeting, the ministry of education officials asked me what Switzerland's formula is for its excellent, inclusive schools. Education officials in Jordan, on the other hand, were interested in how Swiss schools manage multilingualism and a decentralised education system. The Jordanian ministry of education is also keen to introduce a decentralised education system, and the SDC intends to assist it in this task. Our expertise in the Swiss school system is clearly in demand abroad. From their perspective, the question is: how do the Swiss do it and what can we learn from them? The SDC's role is that of a facilitator that creates links between education officials in Switzerland and Jordan.

Precisely because the Swiss school system is decentralised and set up differently from one canton and commune to another, it offers a toolbox of solutions to meet a variety of development challenges in different contexts. Decision-makers can choose the approaches that best suit their local circumstances: school curricula that reflect the local context, getting parents involved, integrating refugee children – Ukrainian refugees enrolled in local schools within a few days of their arrival in Switzerland are a good example – or bilingual schooling such as in Biel/Bienne.

What does the SDC want to achieve?

Our aim is to improve development cooperation and educational outcomes by harnessing the untapped potential that Switzerland has to offer. For example, why should a teacher training college in Mali only get support from NGOs? A partnership between the Malian education authorities and a Swiss university of teacher education could facilitate exchanges between education experts and bring fresh perspectives to educational institutions in both countries. Change requires rethinking established practices and embracing new ideas, not recycling what's already in place.

This initiative is in line with the added value criterion set out in the current IC strategy. But it's worth noting that quite independently of the IC strategy, we had already recognised this potential in 2017 and commissioned studies on the added value the Swiss school system could bring to international coperation. The studies confirmed our expectations. We're now applying the findings of these studies.

Are there any concrete examples of existing links between Swiss IC and the Swiss school system?

The SDC is setting up a major school education programme in Jordan, for example. Numerous development cooperation actors are working on the ground: NGOs, other donor countries and international organisations. We asked ourselves how Switzerland could carve out a niche in Jordan and what added value it could bring to the country. The Jordanian ministry of education had recently announced its policy of decentralising the education system. This is where Switzerland, with its own experience of a decentralised school system, can come in. Unlike other donors or the World Bank and the EU, we have a clear understanding of what a decentralised education system involves and how to organise it, right down to the classroom level.

West Africa is another example. In many African countries, the language of instruction from the first day of primary school is French, which is not the children's mother tongue. As a result, children can't understand what they're being taught, parents don't see the point of sending their children to school and all too many either drop out or learn next to nothing despite years of schooling. Numerous studies have shown that children who don't understand the language used in the classroom in their first years of school struggle with long-term consequences such as poor marks and learning gaps. The SDC works to ensure that children are taught in their mother tongue. For example, in various SDC projects in Mali, Benin and Chad children start school in their mother tongue and French is gradually added later to the curriculum.

What challenges is Swiss development cooperation facing the field of education?

Even before the pandemic, over 250 million children had no access to schooling. It's estimated that since then, another 20 million children worldwide have been denied an education because of covid-related school closures. This mainly affects girls who have been withdrawn from school and forced into marriage or prostitution.

At the same time, state education budgets, which were small even before the pandemic, have been cut further. But in development cooperation as in other areas, the pandemic has meant that donor countries are diverting funding from education to other sectors. Investment in basic education is declining worldwide overall. At the same time, however, more money is being invested in post-compulsory education such as vocational education and training and higher education. If current demographic trends continue, 50% of the population of Sub-Saharan Africa will be under 15 by 2030. Combined with underperforming school systems, this could result in a critical educational gap for generations of children and young people. Once a child falls behind it's nearly impossible for them to catch up.

Lack of schooling has been shown to have negative individual, social and economic consequences.

Education is of strategic importance to Swiss foreign policy

To ensure the effectiveness of its foreign policy, Switzerland adopts a coherent and strategic approach. In line with the priorities of its Foreign Policy Strategy 2020–23, Switzerland promotes equal access to education under its International Cooperation Strategy 2021–24. Ensuring and protecting high-quality basic services – especially in relation to the right to education – for the most vulnerable people affected by crises, armed conflict, forced displacement and irregular migration is a priority of the strategy. Education is an investment that pays dividends for individuals as well as for the reconstruction of crisis-hit countries.