- Home

- FDFA

-

News

- News overview

- Press releases

- Dossiers

- Speeches

- Interviews

- Flights of Department Head

-

Press releases

Press releases

Article, 21.11.2014

The use of rape as a weapon of war is a phenomenon as old as war itself. Since 2008, the UN has actively striven to put an end to this intolerable crime. This is an interview with Zainab Hawa Bangura, the United Nations Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict.

Ms Bangura, you have been the Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General since 2012. Has sexual violence always occurred during conflicts?

Rape in wartime is as old as war itself. You find it everywhere in the history of humanity: even the Bible and the Koran mention it. The challenge is to make the world understand that it is a crime. It is not merely a case of men wanting to prove their manhood; it is not a random act perpetrated by just a few individuals; and it is not some inevitable collateral effect of war. Rape is premeditated, planned and executed. It is one of the tactics of war. Various studies and the efforts of a large number of women have finally brought this issue to the attention of the UN Security Council.

What is the UN doing to put an end to sexual violence in conflicts?

In 2008, the UN adopted a series of resolutions designed to make sexual violence a central issue for the institutions responsible for ensuring international peace and security. For the past six years, the United Nations has worked relentlessly to set up a global legal framework aimed at fighting the impunity of the perpetrators of sexual crimes in past or ongoing armed conflicts.

What is your role in this fight?

My office combines and coordinates the work done by the various actors involved: public health authorities, humanitarian aid and development cooperation organisations, and international bodies responsible for peace and security. We work hand in hand with governments and offer them our support. We must make the perpetrators of such atrocities understand that they will be punished for their acts. And we want to show the victims that we are by their side to offer them the medical assistance, psychosocial support and legal aid they need. In every country I visit, one of my priorities is to listen to victims and restore their hope of seeing justice done. In countries experiencing or emerging from a conflict, the justice system has broken down. So one of my office's priorities is to help these governments rebuild their judicial systems – solid, independent systems which respect women's rights, because a society that does not respect women's rights in peacetime won’t treat them good in times of war. We also dispatch experts to different countries to analyse the legislation there.

Have you managed to discern any positive developments in recent years with respect to how governments perceive the problem?

Yes, the world has woken up and realised that these crimes are real and have a deep impact on the people affected by them. Today, 155 countries have pledged to fight sexual violence in conflicts. One of our priorities is to strengthen the political will to fight this scourge. For example, we have signed agreements with the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Somalia and South Sudan. So there is hope.

Discussions are under way on the objectives for sustainable development post-2015. Why does eradicating sexual violence in conflicts constitute a key element in the fight against poverty and in sustainable development?

Sustainable development and the fight against sexual violence are like the pedals of a bicycle: both are needed for it to work. A society cannot emerge from poverty and reach its full potential if it excludes and crushes the women who comprise 50% of its population. Sexual violence is directly responsible for what has been described as the "feminisation" of poverty. A woman who has been raped and then rejected by her husband and her community, who has no access to land and no other form of revenue, cannot feed and educate her children. She finds herself in an extremely precarious situation. Breaking this circle of sexual violence and meeting victims' urgent needs will enable women to remain integrated in their society and contribute towards sustainable development. So eradicating sexual violence in conflicts is a vital issue for the post-2015 agenda.

What consequences does sexual violence in wartime have on societies and on long-term reconciliation?

Women who have been raped are still stigmatised and often rejected for reasons of honour. Therefore, when a woman is raped, the spirit of a community is destroyed, and women are targeted with this in mind. This is also why forgiveness becomes very difficult, throwing down a major challenge for reconciliation and sustainable peace because the collective memory persists. Moreover, women who become pregnant as the result of being raped give birth to children who will always remind them of the violence to which they fell victim.

What becomes of these children?

In a hospital for orphans that I visited in the Democratic Republic of the Congo I found 260 children abandoned by their mothers, who had not wanted this living reminder of their rape. The fate of these children born of rape was covered in the Secretary-General's latest report. In Bosnia, these children are now adolescents, and we intend to produce a study seeking to understand what has become of them, how they live, what opportunities they have and which challenges they face.

What role can women play in conflict resolution and peace processes?

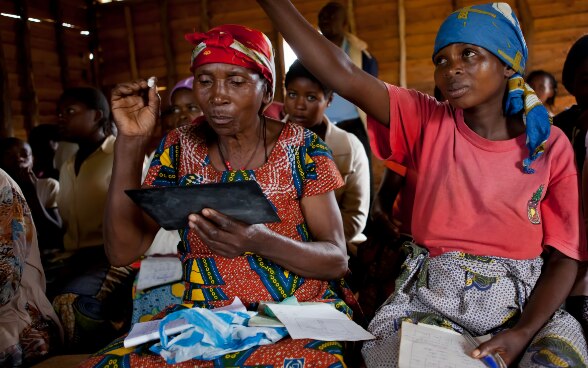

Throughout the world, women raise critical voices, act to ensure peace and serve as agents of change. They have an ability to bring people together and play a peacemaking role, at both the family and community levels. However, often they are not allowed to take part in discussions that directly concern them. Even today, peace processes often boil down to meetings between men who redistribute power among themselves. Yet we could envisage a different kind of peace process, and it is in the interests of families and communities that women be allowed to participate in them. To this end, more women need to be trained to do so. In those peace processes in which the UN is fully involved, we must ensure that their voice is heard. For example, we succeeded in making sure that women and victims are involved in the ongoing peace process in Colombia.

Gender equality is a recurring theme in all SDC projects, and preventing sexual violence and protecting women against it is a core element of Swiss cooperation. Via its National Action Plan on Women, Peace and Security, Switzerland is committed to implementing Resolution 1325, which underlines how women are disproportionately affected by armed conflicts. What can Switzerland do to protect women and girls in conflict situations more effectively?

Switzerland is displaying leadership in the promotion of gender equality, having played a pioneering role by urging other countries to apply the UN resolutions against sexual violence. In 2007 it sent out an important signal to the world by adopting an ambitious National Action Plan. I would encourage all countries to adopt similar provisions, as this would enable us to move forward, from resolutions to solutions. Where Switzerland can improve is in the support it offers victims. Almost 20 years after the end of the conflict in Bosnia, fewer than 20 people have managed to bring their case to court, whereas the number of women raped is estimated at between 40,000 and 50,000. And this example is no isolated case. Switzerland must be mindful of the fact that sexual violence is a feature of all current crises, from Syria to Iraq, Darfur or the Central African Republic. In these crises it is important not only to consider the humanitarian aspect, but also to take action to help women who have been abused.

Impunity is one of the biggest challenges in the fight against sexual violence. How can this problem be solved at the national and international levels?

A clear message has to be sent out to the people who commit these crimes: whoever you may be, we will get you! But for that to be achievable, governments must take their responsibilities. Many of those who indulge in such acts are simple soldiers who have been ordered to commit these crimes. This is why, at both the national and international levels, we must work together to put an end to impunity. In some countries, raping women during a conflict is still not considered a crime. Another problem is that police often lack the training and expertise required to investigate these crimes. And judges are neither familiar with humanitarian law nor human rights. So we must support these governments at several levels.

What is your message to the Swiss public on the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women?

I believe that everyone can play a role to end the violence against women. If you have pupils or children, teach them not to be violent. If you are a politician, violence against women should be one of the issues on your mind. If you are a journalist, write about the topic. Whether male or female, you can help to change people's mentalities. We all have a responsibility to try and solve this societal problem. We must also fight against the stigmatisation of women who have been raped, so that they can come out of the shadows and stop feeling ashamed and fearful. We must restore their hope and provide them with an education so that they can become aware of their rights. For the more confident a woman is in her capabilities, the less likely she is to be subjected to violence. The International Day on 25 November has important symbolic significance. It is an opportunity to convey the message that women's empowerment is essential.

Last update 19.07.2023

FDFA Communication

Federal Palace West

3003 Bern

Phone (for journalists only):

+41 58 460 55 55

Phone (for all other requests):

+41 58 462 31 53